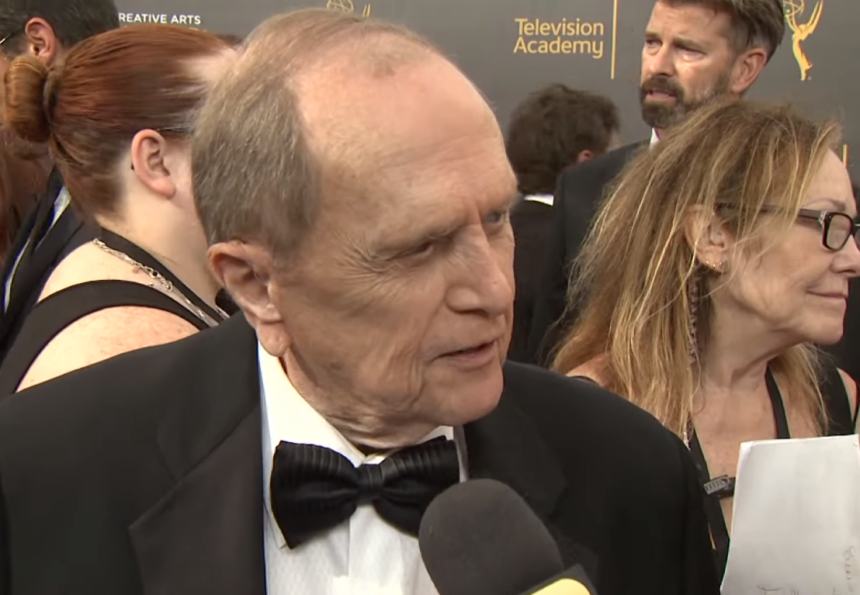

LOS ANGELES — Bob Newhart, the classic comedian known for his sarcasm and peculiar comedian style, passed away at the age of 94. Bob Newhart was born on September 5, 1929, in Oak Park, Illinois, United States. Bob Newhart became the limelight because of his stand-up comedy and television shows

Bob Newhart died on Thursday in Los Angeles after a series of short ailment. Jerry Digney, Newhart’s PR person.

Bob Newhart, started his career in the late 1950s and produced the two super-hit television shows in the 1970s and 1980s. He gained the attention of the audience in the 1960s when he was seen on vinyl “The Button-Down Mind” which later won the Grammy Award.

While many comedians like Lenny Bruce, Mort Sahl, Alan Lord, and Mike Nichols and Elaine May, regularly got laughs with their bold attacks on modern values, Newhart stood out. He had a modern perspective, but rarely raised his voice above a hesitant, almost stuttering delivery. His main prop was a telephone, which he used to pretend to have a conversation with someone on the other end of the line.

“Do you mean to say that you changed ‘four score and seven’ to ’87’?” Newhart asks in dismay. “Abe, the original phrase is meant to be attention-grabbing… It’s similar to Mark Antony’s speech, ‘Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears.'”

Another favorite is “Promoting the Wright Brothers,” in which he tries to persuade the aviation pioneers to start an airline, despite acknowledging that the short distance of their first flight could be a limitation.

“Well, you see, that will impact our journey to the Coast if we have to land every 105 feet.”

Newhart was initially hesitant to commit to a weekly television series, fearing it would overexpose his material. However, he accepted an attractive offer from NBC, and “The Bob Newhart Show” debuted on October 11, 1961. Despite winning Emmy and Peabody awards, the half-hour comedy series was canceled after just one season, which became a source of jokes for Newhart for many years to come.

He waited 10 years before starting another “Bob Newhart Show” in 1972. This one was a sitcom with Newhart playing a Chicago psychologist living in a penthouse with his school teacher wife, Suzanne Pleshette. Their neighbors and his patients, notably Bill Daily as a airline pilot, were an eccentric, neurotic bunch who provided a perfect contrast to Newhart’s dry wit.

The 1970s series, which was highly acclaimed, ran until 1978.

After four years, the entertainer launched another show titled “Newhart.” In this series, he portrayed a successful New York writer who decides to reopen a long-closed Vermont inn. Similarly to his previous show, Newhart played the role of a quiet, sensible man surrounded by a group of quirky locals. The show was a huge success, lasting eight seasons on CBS.

The show ended in a memorable way in 1990, with Newhart – in his old Chicago psychologist character – waking up in bed with Pleshette, sharing a bizarre dream in which he was a innkeeper in a crazy little town in Vermont. This was a parody of a “Dallas” episode where a character was killed off, only to be revealed to have been in a dream.

Two of his later series, “Bob” in 1992-93, and “George and Leo” in 1997-98, were not as successful. Despite being nominated several times, his only Emmy came for a guest role on “The Big Bang Theory.” “I guess they think I’m not acting. That it’s just Bob being Bob,” he whispered about not winning TV’s highest award during his prime.

Throughout his career, Newhart also appeared in several films, usually in comedic roles. Some of these films include “Lost Without You,” “In and Out,” “Legally Blonde 2,” and “Elf,” in which he played the father of Will Ferrell’s adopted full-sized son. His later work included “Horrible Bosses” and the TV series “The Accountants” and “The Theory of How Things Came to Be,” a spin-off of “Young Sheldon.”

Newhart married Virginia Quinn, known to friends as Ginny, in 1964, and was with her until her death in 2023. They had four children: Robert, Timothy, Jennifer, and Courtney. Newhart was a frequent guest on Johnny Carson’s show and liked to tease the thrice-divorced “Tonight Show” host that at least some comedians enjoyed long-term marriages. He was particularly close with fellow comedian and family man Don Rickles, whose raunchy insult humor contrasted greatly with Newhart’s genteel comedy.

“We’re apples and oranges. I’m a Jew, he’s a Catholic. He’s serene, I’m a yeller,” Rickles told Assortment in 2012. After 10 years, Judd Apatow would honor their companionship in the short narrative “Sway and Wear: A Romantic tale.”

An expert of the delicately mocking comment, Newhart got into parody after he became exhausted with his $5-an-hour bookkeeping position in Chicago. To relax, he and a companion, Ed Gallagher, started making interesting telephone decisions to one another. Eventually, they decided to record them as satire routines and sell them to radio stations.

Their efforts failed, but the recordings caught the attention of Warner Bros., which signed Newhart to a record contract and booked him into a Houston club in February 1960.

“An unnerved 30-year-old man left the stage and played his most memorable dance club,” he recalled in 2003.

Six of his routines were recorded during his two-week date, and the album, “The Button-Down Mind of Bob Newhart,” was released on April Fool’s Day 1960. It sold 750,000 copies and was followed by “The Button-Down Mind Strikes Back!” At one point, the albums ranked No. 1 and 2 on the sales charts. The New York Times in 1960 said he was “the first comedian in history to come to prominence through a recording.”

In addition to winning the Grammy award for album of the year for his debut, Newhart also won as the best new artist of 1960, and the sequel “The Button-Down Mind Strikes Back!” won for best spoken word comedy album.

Newhart was booked for several appearances on “The Ed Sullivan Show” and at clubs, concert halls, and college campuses nationwide. However, he disliked the clubs because of the bothersome drunks they attracted.

“Every time I have to get offstage and handle one of those birds, it disrupts the routine,” he said in 1960.

In 2004, he received another Emmy nomination, this time as a guest actor in a drama series, for a role in “E.R.” Another honor came his way in 2007 when the Library of Congress announced it had added “The Button-Down Mind of Bob Newhart” to its archive of significant sound recordings.

Newhart made the bestseller lists in 2006 with his memoir, “I Shouldn’t Do This!” He was nominated for another Grammy for best spoken word album (a category that includes audiobooks) for his reading of the book.

“I’ve always compared how I treat the person who is convinced that he is the last rational man on Earth… the Paul Revere of psychotics going through the town and shouting ‘This is crazy.’ Yet nobody pays attention to him,” Newhart wrote.

Born George Robert Newhart in Chicago to a German-Irish family, he was called Bob to avoid confusion with his father, who was also named George.

At St. Ignatius High School and Loyola University in Chicago, he entertained fellow students with impersonations of James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, Jimmy Durante, and other stars. After earning a degree in business, Newhart served two years in the army. Returning to Chicago after his military service, he entered law school at Loyola, but ultimately dropped out. He eventually found work as an accountant for the state unemployment office. Bored with the work, he spent his free hours performing at a stock company in suburban Oak Park, an experience that led to the phone bits.

“I wasn’t part of some comic conspiracy,” Newhart wrote in his memoir. “Mike (Nichols) and Elaine (May), Shelley (Berman), Lenny Bruce, Johnny Winters, Mort Sahl — we didn’t all gather and say, ‘Let’s revolutionize comedy and tone it down.’ It was just our way of finding humor. The college kids would hear mother-in-law jokes and exclaim, ‘What the hell is a mother-in-law?’ What we did reflected our lives and engaged with theirs.”

Newhart continued to make occasional TV appearances after his fourth sitcom ended and vowed in 2003 that he would continue working as long as he could.

“It’s been so much, 43 years of my life; (to stop) would be like something was missing,” he said.